15 February 2023

Embedding equity in community engagement

By Isha Matous-Gibbs, Social Health and Wellness Planner

Community engagement is a core part of civic engagement. It is a foundation of democratic societies that the public be participants in decision-making.

Governments, corporations, non-profits, and academia regularly reach out to ask people about their communities, their visions for the future, and what challenges they are facing. Who gets invited, which voices are heard, and how their information is used are in part determined by existing and historical power structures.

These structures have been used to suppress some people, while also elevating other with unearned power. This requires that the latter be actively challenged in our society through Justice, Equity, Inclusion and Diversity work, Accessibility Work, BIPOC rights and activism, Reconciliation, and more. Challenging power and privilege to dismantle oppressive structures is a key process in undoing harm and creating a more equitable future.

As a foundation for this work, we need to start by engaging with people who have been impacted by the current systems and find out about their experiences, where their barriers are, and how we can help to overcome those barriers. As community practitioners, that means we also need to elevate those voices into spaces of decision-making and ensure that there is accountability within systems and structures to what is heard as a result.

To do this, our team at Urban Matters CCC has been working on creating a comprehensive set of practices for conducting engagement with People with Lived and Living Experiences (PWLLE). Our set of practices includes strategies for engagement that start with assessing the readiness of the organization to work alongside PWLLE, incorporating their input, and empowering them to shape outcomes.

Our working definition of engaging with People with Lived and Living Experience is the intentional partnering and listening with individuals, families, or communities that have direct experience and insight to support overall improvements in quality, equitable access, and outcomes.

There are many benefits to engagement with community members who have lived experience of a subject. For example, it can:

- Improve the outcome of projects

- Develop trust and loyalty by encouraging PWLLE to take an active and influential role in decision-making for their own health and wellness

- Produce opportunities for PWLLE to shape the projects and policies that will most affect them

- Create more equitable relationships between decision-makers and the public

- Empower PWLLE to feel included and equal in their community

As our work centers around housing and homelessness, substance use, and social determinants of health, this often means that we are working with people who have experiences of homelessness, poverty, substance use, poor health, diverse abilities, and stigma. It also means we are working with people who are resilient, passionate, and skilled at telling their stories. We have the honour of hearing about some of the most painful, and some of the most joyous aspects of people’s lives.

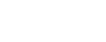

To do this work takes skill and awareness of who we are and how we show up. Many of our partners ask how we do this work, often with an apparent sense of concern about getting it right. We posit that there is no perfect method, no way to make sure we get it right every time. However, there are practices, guiding principles, and skills that can be developed to support a journey of growth and discovery in engaging with diverse people. These can be described as the micro, meso, and macro areas of practice that we work to cultivate.

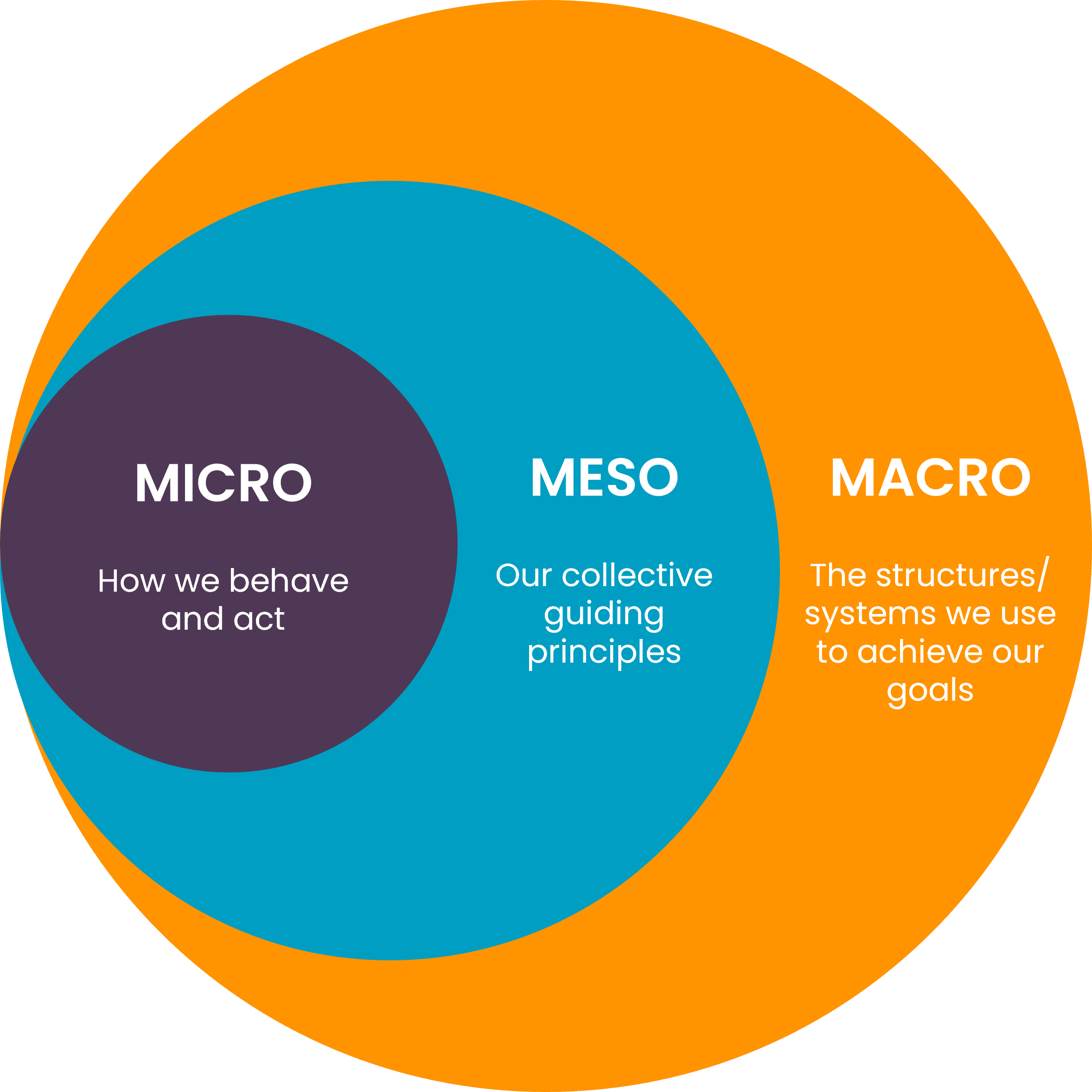

At Urban Matters, we engage in a way that demonstrates a trauma-informed, critically reflexive, and intersectional approach.

Trauma-informed

When we talk to people, we strive to create safe spaces to share with them. The topics we are discussing are personal and are an ongoing part of people’s experiences, which can bring up strong feelings. We recognize that talking about power can be hard, and that sharing personal experiences of powerlessness can be harder. As consulting practitioners, we get to disengage from the subject matter at the end of a project. For participants, the projects and engagements we conduct have implications for their daily lives. We make engagement spaces safe by:

- Being transparent from the start about the process and possible outcomes

- Providing options for follow-up support if needed

- Carefully considering which questions we ask and how we ask them

Critically reflexive

Talking about power means we must acknowledge and understand the power dynamics we are involved in. As individual practitioners, we are committed to doing the personal work of understanding who we are, what privileges and power we hold, and the biases and assumptions we carry with us. Slowly dismantling these takes time and energy. It is not a linear journey, and we are committed to staying on the path. Our practice, then, is to make sure that power and privilege are acknowledged when working with our partners so we can have honest conversations about how to remove barriers to community members.

Intersectional analysis

Everyone has multiple overlapping identities and experiences. Recognizing that individuals cannot be distilled down to a single facet of their identity, intersectional analysis addresses the complexity of the layers of experiences people have. For instance, a white woman may be restricted by her gender but has the advantage of race, while an Indigenous woman with a physical disability is disadvantaged by her gender, ability, and her race. Without considering intersectionality, actions that aim to address injustice towards one group may end up perpetuating systems of inequities experienced by other groups.

Conducting engagement

Many questions come up about how to conduct engagement with People with Lived and Living Experiences. Outlined below are a few easy steps that can be taken to make sure that a project builds trust and rapport and encourages civic engagement by all community members.

- Seek out the voices of people who are not often heard. Take the time to identify who may be left out of engagement and why. Adjust your approach to reduce barriers.

- Ensure there is a clear process for how the findings of engagement will be used to inform decisions. For people who have had negative experiences or who have felt excluded from previous engagements, there is a risk that failure to demonstrate the impact of their input can cause further alienation. Start by identifying which questions and decisions you want input on and communicate this to participants.

- Be willing to make space by giving up power, even though it can be scary to let go. Identifying the decisions that you are willing to let others make (and pushing yourself to find more of them) can generate interest in participation. By allowing new voices in decision-making, we can all learn more.

- Be curious. Taking an equity-based approach to engagement isn’t an easy list of dos and don’ts. It is a process of self-learning and reflection coupled with shifts in organizational practices. Be patient and kind with each other along the way. Approaching the work with a curious mind can help reduce our own internal blocks and fears about addressing our own power and privilege.

Resources for further learning

Trauma-informed engagement has a long history in health work. This article explores how and why a trauma-informed, intersectional, and critical reflexive approach is important.

PEEP Best Practice Guidelines.pdf (bccdc.ca)

The BC CDC worked with peer groups across the province to create a guide for working with people with lived and living experiences of substance use. This guide provides a solid grounding in best practices.

Engaging persons with lived experience | RNAO.ca

The Registered Nurses Association of Ontario has compiled a set of resources for helping organizations prepare for and execute engagement with people with lived and living experiences. These tools can be used to assess organizational readiness, plan for engagements, and learn useful skills.